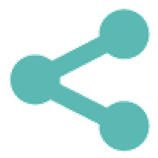

The Search Process

Whether an organization hires a consultant or conducts its own search, the process is similar and can be divided into three phases: preparation, due diligence, and selection.

These three phases likely will take at least three months to complete. (Expect a longer-time horizon for an institution-led search unless the organization is highly motivated, has ample time and staff to dedicate to the project, and is willing to stick to a schedule.)

Phase One: Preparation for the Search

Identify Selection Team: Internal Selection Committee (+ Search Consultant?)

The organization must first decide whether to hire a search consultant or conduct the search itself. In either case, it makes sense to identify a subset of the organization’s key stakeholders (e.g., a selection committee) to lead the effort. The selection committee typically includes various members of the investment committee and one or two members of the board of directors and senior management. A good number for the selection committee is between five and 10 persons.

Note, however, that while the selection committee can lead the effort, it is critically important that the entire investment committee (and, in some cases, the full board) be involved at certain key points of the search process. The relationship between the organization and its chosen OCIO is more likely to succeed if all key stakeholders feel ownership of the search process and the candidate that is ultimately selected.

For example, if the organization decides to hire a search consultant, the selection committee may conduct the first round of consultant interviews, but the entire investment committee should meet the final two or three candidates and prepare a recommendation for a further decision by the full board. (Some suggestions for hiring a search consultant can be found here and here, as well as in this Toolkit.)

Determine Goals and Requirements

Ideally, by this point, the organization already has discussed and agreed on what it wants in an OCIO, based on an internal review of the organization’s overall condition, investment goals, and the needs of the investment committee. (If not, some suggestions on how to conduct this review are set out here, and you also may find this Toolkit helpful.) Although it is normal for an organization’s priorities to evolve somewhat during the search process, arriving at a basic consensus at this stage is important: a search is not likely to be successful if the selection committee is not clear on its main objectives.

If the organization has hired a search consultant, sharing the results of the internal review will help get the consultant up to speed quickly. The consultant’s time in this phase is better spent refining the search committee’s objectives in focused conversations than defining them from scratch through lengthy interviews. The search consultant and the search committee then come to an agreement on the specific services to be provided by the consultant and how much the search committee would like to be involved in phases two and three of the process.

Establish Process Details and Timeline

Based on the organization’s goals and requirements, the search consultant (or, in the case of a self-directed search, the search committee) puts together a list of action items, deliverables, and a timeline for execution.

Phase Two: Candidate Due Diligence

Identify "Semi-Finalists"

The method of identifying a first round of providers to contact (the “semi-finalists”) differs substantially based on whether the search is consultant-led or self-directed.

Consultant database. A search consultant maintains a database of potential providers informed by its experience in prior searches, ongoing research, and the career history of its principals. The consultant uses this database to create a list of between five and 10 candidates that best satisfy its understanding of the organization’s goals and requirements. (Note: If you have selected a search consultant that is affiliated with or receives fees for referrals from providers, you will want to ask whether that is the case with any of the providers on the list.)

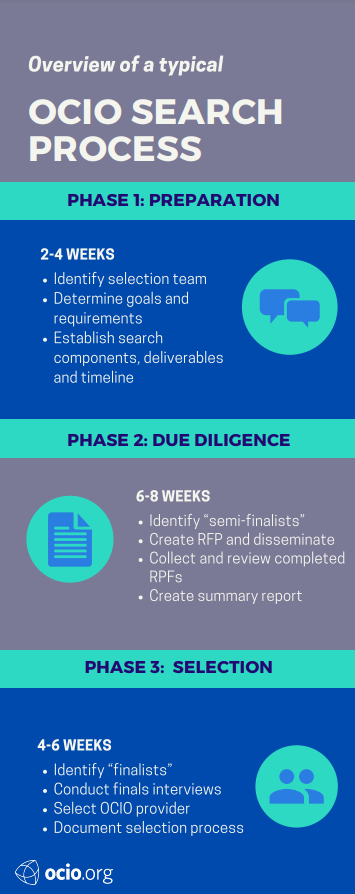

Request for Information (RFI). An organization conducting its own search will not have the benefit of a consultant database and, therefore, must find another way to identify a group of ”semi-finalists.” Most organizations create and issue an RFI for this purpose. An RFI is a relatively short and targeted list of five to 10 questions (as compared with a longer Request for Proposal (RFP) which is discussed further below). The goal of an RFI is to eliminate candidates that don’t satisfy the organization’s essential requirements before sending out an RFP, and to save time that would otherwise be spent reviewing a greater number of lengthy RFP responses (which typically range from 75 to 100 pages in length). A search committee that is already reasonably familiar with the marketplace of OCIO providers may send as few as 10-15 RFIs, whereas a committee with less knowledge may need to send up to 30 (as more of the recipients are likely not to fit the bill). The search committee then reviews the responses to the RFI and, like a search consultant, narrows the list to between five and 10 semi-finalists.

Create RFP and Disseminate

The next step is to create an RFP and send it to the semi-finalists. If the goal of an RFI is to eliminate unsuitable providers, the goal of an RFP is to illuminate promising providers by gathering as much meaningful information as possible about their business models and services. A typical RFP consists of between 25 to 50 questions. How many and what types of questions to ask requires a careful balance; Too many questions will result in an overwhelming amount of information and too few will not provide enough to distinguish the candidates. A consultant is likely to start with its standard RFP template and then add/subtract questions based on what it believes to be the organization’s particular priorities.

A well-crated RFP will elicit information in the context of what the organization needs. An RFP that contains only generic questions will result in stock answers. We suggest asking the candidates some questions focused specifically on the organization (e.g., What specific changes would the candidate recommend to the organization’s existing investment policy/strategy? How would the candidate handle the organization’s specific legacy investments?). Please note that, in order to answer these questions, the organization will need to share relevant details of its current investment program, such as the size, number, and types of its existing investments and how they are implemented.

Important RFP Focus Areas. Ideally, all questions in an organization’s RFP will address important concerns. However, there are a few areas of inquiry where it pays to be particularly probing, both with respect to the way the questions are asked and answered.

If you are concerned about choosing a true OCIO – and we think you should be – make sure your questions regarding potential conflicts of interest are carefully worded. Some candidates may attempt to obscure their conflicts with answers that omit critical information if the disclosure of that information technically is not required by the form of the question (e.g., a combined consultant/OCIO may answer questions only from the perspective of the OCIO division, without disclosing the inherent conflicts that result from its relationship with the consultant division).

Ask directly whether the organization will get proportionate access to all of the candidate’s managers – especially those with limited capacity – vis-à-vis the candidate’s other clients (regardless of client AUM). Don’t settle for vague answers about “allocation policy.”

There are numerous ways that candidates may try to game questions regarding performance. Some providers may even refuse to provide performance information, stating that performance varies based on a client's situation. This is not an acceptable answer. We believe that performance reporting should be GIPS-compliant. At the very least, however, make clear that performance reporting should include only actual results of actual clients. Also, ask for figures that are net of all fees, that include both total return and specific asset class composites, and that exclude non-discretionary accounts and legacy investments. Review any performance reports provided to make sure that all discretionary clients are included in at least one appropriate composite (to avoid cherry-picking concerns) and that return figures are compared against appropriate benchmarks (i.e., benchmarks with risk profiles that match those of the composite accounts). And read the footnotes: this may be the only place a candidate discloses key information (e.g., that results are hypothetical, simulated, back-tested, or otherwise not tied to actual accounts; and criteria for account inclusion in a composite). Be especially wary of exceptional performance figures and rerun the numbers: a claim of exceptional performance demands exceptional empirical support!

Require that each candidate state which implementation system(s) it will apply to your organization – and then make sure that the answers provided in the RFP relate to those system(s). (Some candidates talk at length about implementation systems (and related fees, access, etc.) that will not be used to deploy the organization’s assets. Also, require disclosure on the use of any proprietary products, as well as any lockups or limitations on redemptions should you decide to change providers at a later date.

Ask each candidate how it will treat the organization's existing “legacy” portfolio investments. Will it liquidate the entire portfolio and start over? How will it handle illiquid investments, and what fees will it charge for those investments? (Note that, if a candidate does not charge a fee specifically for illiquid investments, it likely will provide little to no assistance with them, and the full burden of monitoring these tricky legacy investments will fall to the investment committee.)

Ask which specific team members will be handling the organization’s account. Some search committees report being “courted” by a candidate’s top professionals, only to be handed to junior staff after the candidate was hired.

Collect and Review Completed RFPs

Once the semi-finalists have submitted RFP responses, the search consultant or the search committee (in the case of a self-directed search) reviews and summarizes the responses in an executive report for the organization’s board. This executive report should:

- compare the services and characteristics (e.g., implementation systems, services, fees, performance, experience with similar organizations, size, and expertise) offered by the respondents;

- analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the respondents with respect to the focus areas described above (conflicts, access, performance, fees, implementation systems, and treatment of legacy assets) as well as any other areas that were noted as particularly important to the organization; and

- recommend a subset of respondents to interview as “finalists.”

If the full investment committee and board have not yet participated in the search process, this is definitely the point at which they should become involved – preferably, by reading the executive report as well as the RFP responses submitted by the recommended finalists. The full committee and board should “kick the tires,” so to speak, of the report and the finalists’ responses, asking questions, checking conclusions, and reading footnotes.

Phase Three: Selection

Identify Finalists

In this final phase, the search consultant or search committee (in the case of a self-directed search) meets with the full investment committee, board, and other key stakeholders to discuss the RFP responses and the findings of the executive report. The purpose of the meeting is to decide on “finalists” (usually three to four) who will then receive invitations to deliver in-person presentations of their capabilities to the full board and key stakeholders at the organization’s offices. Some organizations find that reviewing the RFPs and the executive report – and effectively seeing what is available in the marketplace – triggers a re-evaluation of and change in their priorities. This is a good time to revisit those priorities and either confirm them or adjust the goals and requirements based on what has been learned thus far.

Create Agenda

Before contacting the finalists, the search committee agrees on an agenda for the on-site presentations (with the help of the search consultant, if applicable). This agenda should not be simply a repetition of the RFP questions, but should include areas that would benefit from further elaboration. Ideally, the agenda prompts the candidates to explain specifically how they would manage the organization’s portfolio, perhaps by asking each candidate to present its proposal for the organization’s overall asset allocation and at least some manager detail. You also may want to request that the candidates send the professionals that actually will be assigned to the organization’s relationship, should that candidate be selected.

Finalist Presentations

Finalist presentations – also known in the industry as “beauty pageants” – typically are full-day affairs. The full investment committee, board, and key stakeholders meet the finalists in back-to-back presentations (facilitated by the search consultant, if applicable) that can last anywhere from one to two hours each. This is an opportunity to discuss the agenda items, ask follow-up questions, and assess the “softer” factors of the candidates, such as their demeanor, communication skills, and how they interact with the board.

Measure Twice, Cut Once

The typical one-day finalist presentation format can be tiring and limited. Many organizations report experiencing “search fatigue” accompanied by a strong desire to decide on a winning candidate so that they can be finished with the process. While this is certainly understandable, consider that an OCIO relationship is like a marriage: a presentation lasting an hour or so is a very short time to assess a potential partner who represents a significant investment in trust, time, and money.

We recommend that the search committee schedule a second presentation with the two strongest candidates. We also strongly encourage the search committee to visit the two strongest candidates at their offices where the committee can better assess the depth of the firms and their cultures. Ask to speak to staff members in supporting roles that didn’t participate in the finalist presentations. If additional in-person presentations and visits are not possible, consider scheduling videoconferences.

Select OCIO Provider

Following the finalist presentations – and, preferably, some additional office visits and candidate staff interviews – it’s time for the board to decide on an OCIO partner. Prior to making this decision, the selection committee should make sure it has confirmed the key aspects of the proposed relationship as understood by the organization.

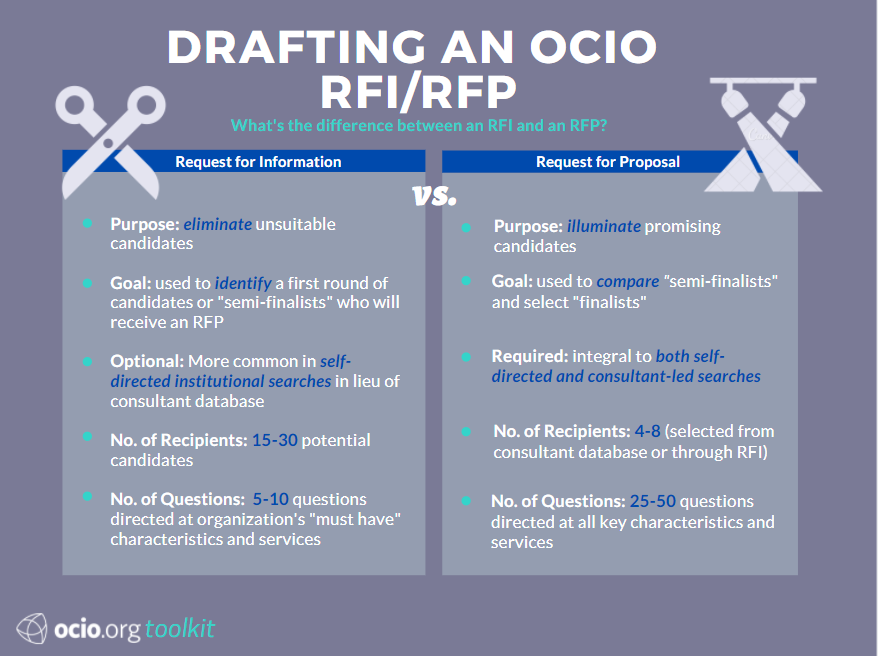

Last Chance! Ten Key Decision Points

Although every organization will have specific requirements, some concerns are universal. Do not make a decision without confirming the following ten key decision points:

- Philosophy. What is the candidate’s investment philosophy? Are there commonalities with how the investment committee thinks? Does the candidate enhance the investment committee’s thinking about the investment portfolio and policy?

- Roles. In the candidate’s proposed implementation model(s), who is accountable for which decisions? Is there any flexibility in areas that the organization believes are important (e.g., manager sourcing, and levels of discretion) or are the relationship parameters fixed?

- Enterprise Risk Management. Does the candidate’s proposal take into account the unique financial condition of the enterprise as a whole, or does it view the investment portfolio in isolation?

- Asset Allocation Approach. Does the asset allocation the candidate puts forward make sense? Are its assumptions overly aggressive or overly conservative?

- Implementation. How will the candidate implement managers in the organization’s portfolio? What vehicle types will be used (i.e., single fund, hybrid, separate account, or combination)? What are the pros and cons of the candidate’s proposed approach given the organization’s size? What will the candidate do with legacy investments – will it look at existing managers first to see if any can be retained, or will the managers be terminated and the holdings sold? What about illiquid legacy investments? How will the candidate engage with the investment committee in this process?

- Potential Conflicts. Does the organization understand all the direct and indirect ways the candidate will get paid for its services? Does the candidate have other business lines or relationships with managers that could result in additional revenue for the candidate? (Note that candidates with these types of conflicts are not true OCIO providers.)

- Access to Capacity Constrained Managers. How does the candidate handle access to capacity-constrained managers? Do all clients get pro-rata access to all of those managers, or are some clients favored? Does the candidate have other business lines that could compete with its services for capacity? (Again, a candidate that has competing business lines is not a true OCIO.)

- Total Organizational Support. What other services does the candidate provide to clients? How will the candidate’s services complement any work done by the organization’s existing team?

- Team. Which investment and client service professionals will the candidate assign to work with the organization? Will they commit to attend meetings? Will the candidate agree to this in the organization’s contract? If not, why?

- Commitment to OCIO Business. Is OCIO the candidate’s only business line? (Note: if it isn't, the candidate is not a true OCIO.) Does the candidate have succession plans in place and a structure where it will be able to serve clients for at least 10 years? How deep is the team?

What About Performance?

You may have noticed that performance is not in the above list of key decision factors.

Why?

Hiring a firm primarily because of past returns is a mistake. It is reasonable to be concerned about a candidate that demonstrates consistently poor performance under different market conditions and through numerous financial cycles. However, if an organization chooses a partner based primarily on exceptional past performance, the relationship will crumble if that performance is not delivered quickly. Some boards report that, in retrospect, they were “blinded” by a candidate’s performance to the exclusion of all else, and that it caused them to view the candidate’s team more favorably than it otherwise would have with respect to unrelated – but equally important – areas, such as integrity, innovation, quality of support services and overall competence.

Also, be wary: If the performance of a particular candidate is substantially better than that of other candidates, we encourage you to review the performance details (and the footnotes!) very carefully. Some firms report performance in ways that are frankly misleading and unethical. Unfortunately, the lack of generally accepted performance reporting standards in the OCIO industry favors candidates whose compliance departments condone reporting techniques that are (in euphemistic terms) “aggressive” and “push the envelope.” A stellar performance history also could be the consequence of willingness to take inappropriate risk with client assets – not superior skill.

Finally, remember that, unlike in some other areas of life, in the financial world: “Past performance is not predictive of future results.” There are simply too many factors at play in the markets, and performance tends to be cyclical.

Document the Selection Process

Make sure the board documents the reasons for its selection. As a matter of good governance and fiduciary responsibility, it is important to keep a record of the board’s due diligence.